Making the lessons -Tech Notes from Double Dee

I'm sure many Double Dee and Steinski fans wonder about the technical side of our early productions. Here's as much as I can remember about the creation of "The Lessons" including our most popular record "Lesson Three - The History of Hip Hop".

Double Dee and Steinski - 1984 Clack Studio B, NYC

At the time of Lesson One’s creation (Fall 1983) I was working at Clack Studios in NYC, a unique commercial studio with a happy family atmosphere, owned and operated by Thomas Courtney Clack - a very colorful character and a cracking engineer. He worked for the BBC before moving to America and brought with him a complete set of BBC sound effects on 7" discs and his ever-growing library of self recorded sounds. I learned quite a lot from him about making and using sfx and foley, producing, and especially how to handle a turntable while making commercials.

I took over Studio B as a sound engineer in 1977 (before we were called Sound Designers) when the clientele was mostly ad agencies and record companies. Almost all the major NYC based labels came to us to produce their promotional record commercials.

The three studios at that time had a complement of a mono 1/4”, two stereo 1/4” and a 4 or 8 track machine (each room was different though), and a turntable for cueing records. What we did different while building a multitrack mix using vinyl was, instead of transferring the songs to tape first, we cued up and transferred the record onto the 8 track directly, saving a tape generation.

When I arrived the machine complement was Scully tape machines in my room, Tom Clack had a mix of Scully and Ampex 1/4” machines in Studio A. Clack Studios didn’t have central air conditioning, but my room had a door leading to a real NYC outdoor terrace big enough for most parties. It was awesome! I even used it to record outside on (and lots of other fun activities).

Door to the terrace, just a few feet from where I sat. Left is RCA Records producer Gregory Bruce holding the mic for David Langston Smyrl getting a true outdoor recording. David later played Mr. Hooper on Sesame Street.

“Humid NYC summers were rough on the equipment. Too often the tape machines would literally stop working”

Of course all the equipment was analog back then. We had to fastidiously maintain those tape machines everyday, cleaning heads, degaussing them, also calibrating the machines was a must. All kinds of NYC polluted crap seeped in through the terrace door and got into all the machines and unfortunately affected the relays in the tape transports.

Humid NYC summers were rough on the equipment. Too often the tape machines would literally stop working and I would have to power down the room, flip up the tape transport, take out the relays and clean the metal contacts with a special sandpaper. If that didn’t work I’d have to scrounge around for substitute relays from machines not in use to get back to work. This was a pro studio, but not a high level pro studio. It was loose, like working in your apartment and we couldn’t afford the luxury of a full-time tech.

Soon after they were first manufactured we took possession of some Otari tape machines. Wow, we were on the cutting edge! They were fast, light, great for editing, and could play backwards (very important for back-timing). So now I had three 1/4” Otaris, convertible mono or stereo. The mono machine was for voice recording, a 2-track for music or sfx playback and the third machine to record the mixes. We replaced the Scully 8 track with an MCI 8 track. I hated that machine. I was constantly having to resort to percussive maintenance to keep it working (banging on the side with my fist). When it did work, it was quieter and handled better than the Scully which tended to be a bit hissy.

Older photo (probably around 1980) of Studio B with Scully 8 track and KLH speakers. On the extreme left is the Technics SP-15 turntable, a real beauty. The Otaris and MDM speakers were a huge upgrade.

The console was a homebuilt affair, designed by myself and technical wiz John Fulleman. John happened to be John Cage’s tech man, so he was a genius as you’d expect. Tom Clack had a gorgeous small API console that I liked and we decided to use API components in a frame that John built. Each channel had a different type of API EQ or API compressors. It was a 12-channel board and each channel had two inputs.

The crazy idea John came up with was to build touch-activated switches out of concentric metal rings with a rubber sleeve for insulation. When you touched one your skin would cause the switch to change inputs, or mute audio. It worked great, until I spilled a beer onto it. It was never quite the same.

John also concocted a method to create presets. And, it sounded great! It had a small speaker built in right in front of the producer desk.

I’ll never forget mixing an MTV mix that was so hot the speaker burned up with a cloud of smoke. Fortunately that never happened to the MDM Time Aligned speakers that were used for the main monitoring.

Around 1982 -Sitting on the 4 track machine on the left is the remote for the MCI 8 track which is in the back of the room. There are 2 additional MDM monitors sitting under the speaker shelf, this is not a normal situation but an experiment, most likely during a session with John Klett. That would be the corner of his Linn Drum Machine on the extreme right.

In the Spring of 1983 Steve Stein arrived at Clack Studios looking to book a session doing a freelance ad job, which fortuitously was scheduled with me. Steve and I quickly became friends finding our love of music to be our bond.

I was always a musical chameleon, loving pop music and interesting sounds, often going with current trends as well as my darker, more teenage love of Euro Prog Rock. And James Brown. And dance and disco. And Basie, etc. Steve brought something new, which was a deeper knowledge of Hip Hop (and Jazz) and more importantly what was going on in the streets and clubs.

I mean, I already loved the early records of the 80s but I was also into Elvis Costello and Dave Edmunds and that whole tribe of Pub Rock. And Yello. And B-52’s. And Jazz. Etc. I was spread out all over, happy to roll around the beat of most anything as long it was good music.

Double Dee's secret mixing method is captured for the first time in this 1985 photo at Intergalactic Studios, NYC

Now the stage is set. I’m making literally thousands of these record commercials for six years, and I was getting real good at making music edits and learning more advanced techniques that didn't require using a razor blade.

Punching-in was one of those methods. No big deal, it was a preferred method of multitrack sound production. I found I could play back a song on the 8 track, cue up a new record like a DJ would, then release and sync the disc while fading up a board fader and recording onto new tracks. But if I didn't record onto a new track and instead punched into record on a track that was playing back - I could do nice and smooth razorless edits.

This way I could create a loop by cueing up and punching in so the recording on the 8 track was continuous. I could loop it as long as needed - again, not having to physically cut the tape with a razor. This technique was key to my "sound". I got as good as you could get at quickly determining the best parts of the record to use, and how to put it all together quickly.

David Witz with Dave Ogrin at Quad Studios NYC during mix of Tastes So Good for Profile Records.

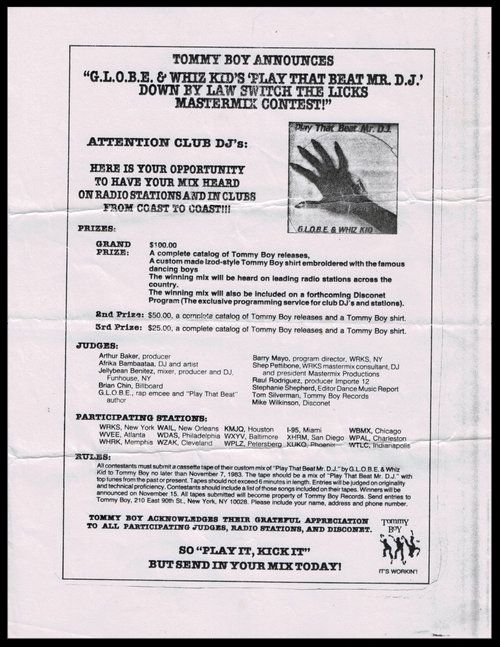

The last piece of the puzzle was David Witz (aka Arthur Ether on the "Taste So Good" 12”), who was good friend and client from CBS Records (read all about Making Taste So Good here). One day he handed me an ad from Billboard Magazine that was announcing a very special contest for DJs. It was the called the "Down By Law Switch The Licks Mastermix Contest" that Tommy Boy Records had put together to advance promotion of "Play That Beat" by G.L.O.B.E. and Whiz Kid (who were members of Afrika Bambaataa's Soulsonic Force).

The rules were simple, take "Play That Beat" and mix it up with anything else you like. If not for that creative freedom we wouldn't have gone down those paths and experiments, which really became our favored way of working. So I called up Steve and literally said, “There’s this contest we’re going to win…”.

original Ad for the Tommy Boy Contest

So, one weekend we gathered up ten crates of records and camped out at the studio until the evening, and again the next day. And that was it, just the two days. After all there was no random access that computers gave us, you really had to work linearly from start to finish. We picked something to begin with (the top of the record) and kept asking “what next?”.

It was a real back-and-forth, and a true collaboration between the two of us - a beautiful creation from our hearts and rumps. Otherwise Lesson One wasn’t different from the work I was doing on a daily basis. But it was new territory and it sparked the discovery of Steve's unique production talents.

I still have the letter Tommy Boy sent out announcing we'd won the contest:

By 1983 samplers were still an exotic toy and we couldn’t afford one so I was using tape edits to emulate an Emulator! Such as the “wha-wha-what’s up Doc” bit in Lesson One . If I were a real DJ I might have scratched it, but I never developed record control to that extent. I was not a DJ by trade, I was a producer. Steve was DJing live sets by this time but he didn’t develop into a Zulu level scratcher either. I did sometimes scrub the tape simulating a turntable - that way you could 'scratch' any recorded material. When we produced The Sugarhill Suite we were lucky to enlist Cut Chemist for some world class scratching. Today we're starting collaboration with ADA who's already added some fine turntable work on several upcoming projects. Interestingly we've never ever used a sampler; I hated the sampler stutter thing that early sampling pioneers felt compelled to do.

Even the "Taste So Good" record I produced with David Witz used tape edits instead of sampling, and I even copied the sampler stutter that I hated so much on the final record. I edited all the voices on 1/4" mono tape and pre-built the vocals before heading into Quad Studios in Times Square to make and mix the 24-track.

The first synchronizer I worked with the BTX Shadow did the job but was a beast to get working. I was so glad to not have to work with tape machines anymore!

This was a time before synchronizing tape machines became prevalent. At the session I had to manually start the playback machine to sync up the vocal tape to the 24 track tape, which would inevitably go out of sync after a short time. So it took valuable mix time to build the master. Because of the slightly imperfect timing, the end result has a special quality that samplers didn't provide. Almost like the Beatles making Sgt. Pepper, except they did rig up a crude sync system on Day In The Life.

During this period the tape machine was my primary instrument and remained so until 1989 when, fed up with the intensive manual editing most jobs required, I discovered and convinced my employer Superdupe Studios to purchase the NED Synclavier and PostPro Tapeless system. But that's a subject for another article.

(edit - Actually I acquired an Akai S900 sampler and used it primarily at the Superdupe. However it's 11.75 second memory was no match to the Synclavier)

A few months after the success of Lesson One's release we decided to create another mix, Lesson Two aka The James Brown Mix.

The workflow for Lesson Two and the equipment were the same as Lesson One, there were no different techniques or effects used. However this time we spent twice as much time in the studio. We started on Saturday February 11 and continued the next day and then the following Saturday and Sunday: a whopping two weekends! These days I'm happy to finish something in two years!

I left Clack Studios to work freelance mid 1984 as a new Sound Workshop Series 34 console was installed and John Terelle took over the room and eventually was one of the original owners of Hothead Studios, the successor to Clack.

Moving forward to 1985, Steve and I were briefly sharing a huge Brooklyn apartment and had quickly put together an 8-track studio. This is where we made Lesson 3, in early 1985.

Quality wise it was down a notch compared to Clack Studio B. The 8 track machine used 1/2" tape instead of 1" tape for one thing, and the Otari 2 track ran at 15 ips instead of the 30 ips that the Otari machines could achieve. But I had 4 channels of DBX noise reduction, so that helped tape noise considerably. I remember adding 3db at 100hz on Lesson 3 for some bad reason, it was probably to make up for the lack of bass response from the Yamaha NS-10 monitors. That bothered me for many years and then Lesson 3 was sold without our consent by a few bootleggers and they released a mix with 60hz hum all over it!

Every studio needs a cat. Well Zoltan had 4! Here's Ollie chilling out on top of the freezer at 3:30 in the AM after a night at the Roxy.

Thankfully I have a digital transfer of the Lesson 3 original 8-track tape which I was able to remix for the 2016 remastered version. Unfortunately, the multi tracks of Lesson One and Two are long gone.

So the workflow was identical to working at Clack Studios except we didn't have to leave home to work. Lesson 3 was the only record we made in that home studio, although we also did a few paying ad type jobs in there. In the end the setup was a considerable cost compared to doing the work digitally today, close to $10k or more with all the synths.

Steinski

The positive thing about working in this manner though is that it forces you to make on the spot decisions on levels, eq, efx, sub mixing. It's more difficult now having today's options getting in the way of making a final decision. Even after you upload your new song you can always change it and re upload.

Without a deadline the process seems to drag on. But then the process is as important if not more so than the product. Once your product is finished what do you do next? I think that's why I have several projects hovering. I'm savoring the process and all it's details. But I promise all will get done!

The Double Dee collection 1985 with him programming a DMX drum machine for some MTV tracks in the upper right.

Part of Steinski's records in the Zoltan studio.

One of the other fascinating things I've learned in this journey is how the tools you use greatly influence the style of the project/product you're working on. We originally were using hands on turntable, tape machines, and razor blades to create and build tracks. That process dictated a linear, beginning to end, method of linking songs and voice bites. Often painstaking when trying to get the timing just right or pitches to match. Sometimes you might have to throw away what you made and start again from the beginning.

Editing on a multitrack tape could also produce some nasty surprises. The razor blades used to cut tape had to be demagnetized, otherwise when cutting tape the action would leave a permanent "bump" sound on the tape. Usually unfixable!

Nowadays, it's remarkably different using computers to manipulate audio. Nonlinear access to audio stored on a hard drive and the ability to slice, dice, and really do anything you desire has created a seemingly infinite amount of choices. This can be a very intimidating experience, and I often have to remind myself how lucky I am to have all this power at my disposal!

That's about it for now. In the future I'll get into our later studios and current workflow. If you have any questions about this article please use the contact form, I'd be happy to pass on more detailed info.

- DD, 11/28/17

Clack Studio B equipment (1978-1985)

- 1 - Otari MTR-10 1/4" full track mono tape machine

- 1 - Otari MTR-10 1/4" half track stereo tape machine

- 1- Otari MTR-10 1/2" 4 track tape machine, with half-track stereo head stack

- 1 - MCI JH110 1" 8 track tape machine

- Custom console, 12-in 2-out, using API 500 series EQ and Compressor modules ( API 550a, 560, 525 Compressors)

- 500 Series Lunchbox with Valley People Gain Brain II and Maxi-Q modules

- MDM Nearfield Monitors

- Technics SP-15 Turntable (Stanton 681 EEE cartridge with Stanton preamp)

- AKG C451 mics, AKG C414 mic

- Eventide 949 Harmonizer - For some reason this was never used on a DDS project

- Tapco - 4400 Dual Spring Reverb

- Orban De-esser

During off-hours I would sometime stick an Altec 604-E cabinet in the stairwell and hang a mic or two about 2 floors down. It was a rich and sweet reverb chamber - I wish I had that today!

Zoltan Studio (1985-86)

Not bad for a home studio. But all this can be replaced with a laptop or even an iPad! I cannot remember what I used as an amp for the NS-10 speakers.

- Ramsa WR-8210 Mixer/console

- Yamaha NS-10 speakers (original not "m" versions)

- Tascam 38 8-track 1/2" tape recorder

- Otari 5050 2-track 1/4" tape recorder

- Technics SP-1200 turntable with Stanton cartridge

- DBX 4-D noise reduction - 4 channels for the Tascam 38

- Valley People Dynamite 2 channel compressor/gate

- 2 Korg SDD-2000 delay/sampler

- ART 01a digital reverb

- Voyetra-8 synthesizer

- Sequential Pro-1 synthesizer

- Roland Juno 60 synthesizer

- Roland CSQ-60 sequencer

- Roland TR-808 drum machine

- Roland TR-606 drum machine

- Roland TB-303 bass sequencer

- Roland SH-101 synthesizer

Roland MC-202 sequencer